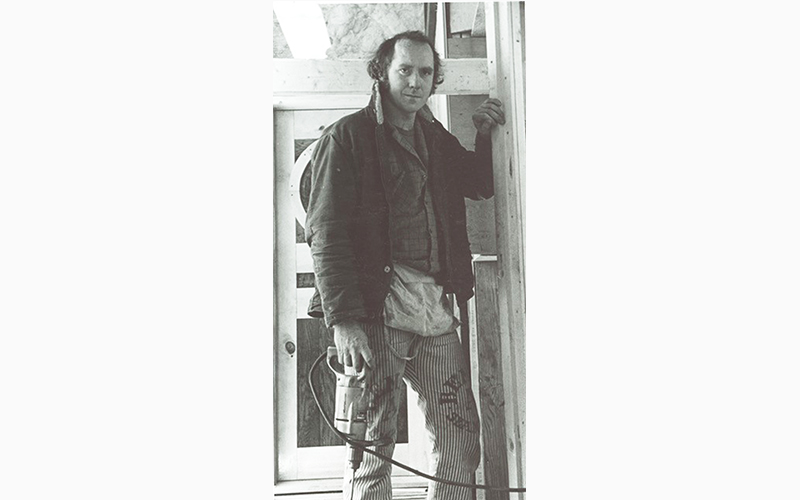

Much like the real estate boom that is going on now, the Mad River Valley experienced rapid growth in the 1960s and 1970s. One of the reasons, was the birth of the design/build movement, which famously transformed our sleepy little community into what has been called The Valley of the Architects. The man largely responsible for the phenomenon is David Sellers of Warren. Now a resident of 57 years, he was declared by Architectural Digest in 1991 to be one of a hundred of the world’s foremost architects.

I’ve known David for over three decades, but never discussed with him his arrival in The Valley or the triumph that followed. As my current research of The Valley focuses on the late 60s and early 70s, it was time to have that talk. He agreed to meet at the Big Picture’s café. We settled in with cocktails and crab cakes, and I recorded our conversation.

“My mother’s sister was my Aunt Helenmarie. But she smoked all the time, and as kids we talked about her smoking. So, she had a nickname -- Mokemarie. After a while it just stuck.

“She had kind of a tragedy when she was young. This relates a lot to what is going on with the women’s movement now. She got pregnant and had to have an abortion. And it went bad. She couldn’t have kids after that. Her sister, my mother, had three boys. She became a kind of surrogate mother to us. She was always there, ready to help all the time. She lived in Chicago, and we were the next town north of Chicago so she would always visit us. And her husband, Mozart Lovelace, Uncle Mo, was a banker in Chicago. Very sophisticated, obviously very successful, very elegant dresser. He and my aunt would travel all around the world. Since they didn’t have kids, they went off and did a lot of other things.

“When I graduated from Yale in 1960, with a degree in mathematics and chemistry, Mokemarie said, ‘Here’s a thousand dollars graduation gift -- go around the world.’ The stipulation was that I had to go alone. And she was right. It was the best thing that ever happened to me. I got on a boat to Europe. To Amsterdam. A cheap boat. On the boat I ran into a guy from MIT, and we entered the evening bridge tournament and won it. Totally illegal because we had invented a way (a code) to talk about the game as we played.

“As soon as we got to Amsterdam, I was off to England because I didn’t speak any of the languages. When I got there, I bought a motorcycle and started traveling around. I realized that I didn’t have a lot of money. Out of the 1,000 dollars that was supposed to get me around the world, I had spent $250 on the motorcycle. I was 21 or 22 years old. When I saw somebody out working, I stopped and volunteered to work. They’d usually feed me. And that’s how I made my way through Europe -- until I had a motorcycle accident.

“But the accident is how I got into architecture. I was on the Pont d'Avignon, going across the bridge and WHAMMO. A car slammed into me, and I was knocked unconscious.

"I remember laying on the ground and a nun came up to me. She had a little silver vial of something that she gave me. Next thing I knew, I woke up in a house. This is 1960. And I was an American. The French at that time loved Americans. They decided to take care of me. They found a woman who spoke English, and she was from Chicago! After the second World War, the United States created opportunities for French soldiers to tour the United States and one of these guys met his future wife in Chicago. They brought me to her house.

“So, this woman took care of me, and someone fixed my motorcycle. Her son was my age and going to the Beaux-Arts School in Grenoble, France. He came home while I was recovering, and eventually we drove around southern France together. He always had a sketch book with him. I asked him, ‘What does it take to be a really good architect?’

“I hadn’t drawn anything since grade school. In third and fourth grades the teachers thought I was really talented. But then the other boys called me a sissy, so I hadn’t done a drawing since then.

“He told me that you had to know your math and science. And I had just gotten my degree in that. He said, ‘You have to have a good imagination.’

“I said, ‘You are looking at Mr. Imagination.’

“He added, ‘You have to be good at drawing.’ I looked at his drawings and thought I could do better. So, I realized that I had everything he had, and I knew that Yale had an architectural program. However, by the end of the summer I was in Denmark about to start across Russia. I could continue on my travels or take a break and see if architecture was for me. In the back of my mind, I thought it was.

“I sent a telegram to Yale asking permission to start classes the next week and that I would wait at the telegraph office in Copenhagen for their response. It never came after a week, so I figured I would go back anyway and sit in on the classes, knowing Yale never took attendance. If it wasn’t for me, back to Denmark to continue across Russia. So, back to New Haven on the Amsterdam, the boat, with my motorcycle. I rented a room for work exchange and started taking classes.

“I loved working on designing things day and night -- between touch football games. It came time for final exams in the fall, and I wanted to stay. I went to the dean’s office to fess up. They laughed and showed me my telegram that they had received but the return address was garbled, so they never could answer me. They looked up my record and decided to take me as several students bowed out at the last-minute making room for me by accident.

“The administration brought all the teachers in and asked, ‘Is this guy any good?’ Apparently, I was. They let me in on probation and I did well. In fact, I went on to be president of the class.”

In the meantime, Dave is the founder of the Madsonian Museum, and they have a new exhibit. It explores how The Valley can grow in a sustainable way to provide more housing options. Check it out.

You can write to me at marykathleenmehuron.com with your favorite memories and story ideas.